On 25th May 2025, it will be the fifth anniversary of the murder of George Floyd. None of us needs to be reminded what happened there.

I’m White British. No getting around it. My DNA a mix of, in descending order percentagewise: English, Scottish, Irish, Welsh, and a pinch each of Swedish and – wow, since I’ve chosen to live in the Azores, what a welcome surprise – Portuguese!

Four – only four – of my truly close friends to date identify as Black, Mixed Race, or a Person of Colour. I also belonged to predominantly Black church congregations when working briefly in Uganda and during the nine years I lived in South Africa – but I’m talking about women with whom I experience soul-baring sisterhood. We don’t necessarily agree on everything, as thinking people don’t. Yet we can feel the mutual love and loyalty.

So, I can make no great claim for my own cross-cultural immersion. But in view of the looming anniversary date, believing as I do in the power of storytelling, and that we become what we read, I’m paying tribute to two standout novels in which Black Lives Matter.

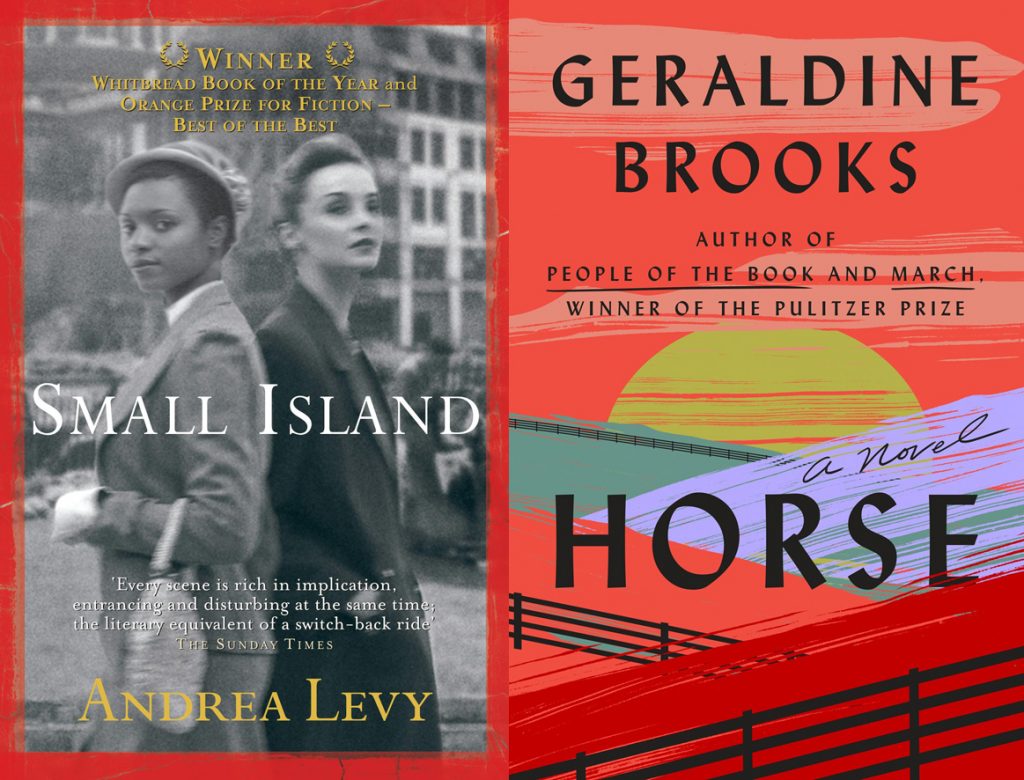

In my first blog post, I alluded to my mid-Atlantic location as a portal. My perch here prompts me to reach more globally for inspiration. On this occasion, in the interest of fairness, I’m exploring English-speaking contexts on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean: Small Island by Andrea Levy is set mainly in Britain during and after the Second World War; Horse by Geraldine Brooks switches between nineteenth century and contemporary America.

These summaries will be tasters because I don’t want to spoil your first-hand engagement with either book.

Small Island, if you will excuse the over-simplification, centres on the interactions of a Black Jamaican couple, Hortense and Gilbert Joseph, on their arrival in London, and their White British landlords Queenie Bligh and her husband Bernard. In the telling of all the main characters’ back stories, the cultural and geographical canvas of the narrative reaches much further.

But above all in her prizewinning 2004 novel, Andrea Levy gives voice to the Caribbean people who settled in Britain from 1948 – the Windrush generation, many of whom the British government would shamefully detain and deport as recently as 2018. An author, drawing on her personal heritage of Black Jamaican, Scottish, and Jewish ancestry, unequivocally possessing the authority for the task.

Horse is the story of Jarret, a Black slave owned by three successive masters in Kentucky and the South in the 1850s and Civil War years, who forms a bond with a thoroughbred foal and trains him to become ‘Lexington’ – the greatest legend in American horseracing history. Paintings by Thomas J. Scott, a White artist loyal to the Union, turn up a century and a half later to shake the dust of forgetfulness off the story of Lexington and his groom.

In 2019, a portrait given away for trash by his neighbour leads Theo Northam, a Black Oxford- and Yale-educated art historian based in Washington DC, to Jess, a White Australian woman tasked with restoring the horse’s unidentified skeleton cast aside in a storeroom at the Smithsonian Museum. Their edgy but tender romance gathers strength.

While the first narrative thread in Horse ends well, the second plotline invokes outrage akin to the kind of real-life murders of which George Floyd’s is only one example.

That Jess has no surname throughout the novel is author Geraldine Brooks’ quiet counterpoint to enslaved people being known only by their master’s surname and their own first name, e.g. ‘Ten Broeck’s Jarret’. I thought I’d spotted it, though I had to go back through the book a second time to be sure this was what she had done.

But is there a snag in Geraldine Brooks’ own White identity? Would it have been better to leave the telling to a Black writer? Cultural appropriation apart – which I think she avoids by narrating the story through the multiple third-person perspectives of the most significant players, never adopting a Black character’s first-person point of view – I get that a White writer is taking up a publishing slot that could have foregrounded a Black novelist.

For your consideration, I offer this analogy. Back in Britain in my teens and twenties, it was the novels of dissident White South Africans Nadine Gordimer and Andre Brink that awakened me to the evil system of apartheid. I knew about it, in theory, from the news and my fellow students’ demonstrations. But fiction thrust the message into my guts and soul.

I’d like to think there’s place for a Geraldine Brooks alongside an Andrea Levy, both writers raising a lamp for awareness.

And what of me as White reader? Just as I am a Straight (a word I feel a touch uncomfortable about, despite its wide acceptance) Ally of the LGBTQ+ community, I hope to be a White Ally against racism.